IMPROVISE. ADAPT. OVERCOME

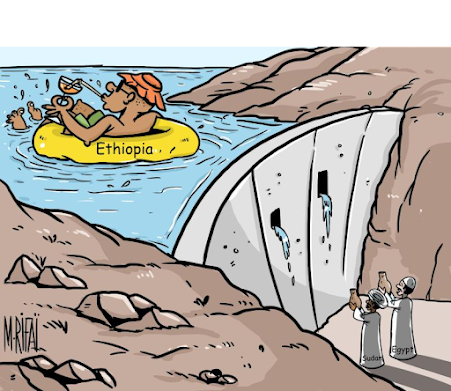

Previously, I explored the positives of GERD, with a major focus on the interdependent nature of Egypt and Sudan on the Nile’s flows. Alongside increasing climate variability, the volatility of the situation will increase, forcing Sudan and Egypt to adapt their water resources to increase food security which is commonly done through three policies: domestic food growth or importing food.

Unless immediate climate change adaption measures are taken, climate change-induced biophysical crop stress might reduce Egypt's food crop yields by 10% by 2050 and cost the economy US$1.84 billion per year (IFPRI, 2021). This has sparked several agricultural projects to expand cultivated land and boost domestic agricultural production (Hamza & Mason 2004).

Urban sprawl on the agricultural land (El Ghorab and Shalaby, 2016)

Toshka Project

With the 1992-2015 urban sprawl destroying almost 75,000 hectares of arable land, the Egyptian to implemented the Toshka project in aims of greening desert lands and creating sustainable environments for agricultural activity. The project consisted of constructing a system of canals to carry water from Lake Nasser, Lake Toshka and the reservoir of AHD to irrigate parts of the Western Desert of Egypt (Baker 1997). Not only did this initiative intend to double the region’s arable land, but also create 2.8 million new jobs away from the narrow confines of the Nile Valley.

However, as seen with GERD, with scale comes challenges, such as:

- Dependence on inadequate foreign investment

- Water leakage

- High costs

- Technical problems

… all leading to its failure (Sims 2015), however all hope was not lost.

More recent methods have had larger focus on the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in the face of climate change, for example “Building Resilient Food Security Systems to Benefit the Southern Egypt Region” which focused on developing adaptive technologies in agricultural production such as rehabilitating canals, allowing farmers to irrigate land more easily and at a lower cost due to the reduced need for pumping. Under the program the farmers saw a 30-35% boost in income and a 25-30% drop in the need for fertiliser or excessive water use.

Virtual Water

Virtual Water represents ‘water that is embedded in crops, livestock, and services; it reflects the total amount of water used to produce goods and services’ (Allan 1998:545–546). By the millennium, the Middle East and North Africa had imported approximately 50 million tonnes of grain, amounting to the importation of 50 km3 of virtual water, equating to the annual flow of the Nile into Egypt (Allan 2005).

Benefits

Despite many Egyptian wheat farmers being forced to switch to other crops, there are still benefit which apply. Wheat prices will dramatically drop, thus many Egyptians who previously couldn't afford it at local prices will now have access to the staple food. Further, the local resources that were being used for wheat production will be reallocated to more profitable/lucrative pursuits (e.g. cash crops, value added manufacturing)(Bargout & Fraser, 2018; Remy and Evan, 2018). This can allow for a shift from net importing to net exporting VW, reducing water consumption, and injecting foreign currency into the country, while also easing political tensions due to a reduced dependency on the Nile as the sole source of water for food production.

However..

..... depending too heavily on foreign imports may affect the Egyptian public's impression of the government's effectiveness, as well as their national identity around their own sovereignty. Water-scarce MENA nations will undoubtedly be price-takers if the VW economy is ruled by cartels of water-rich countries that determine international commodities prices(Warner, 2003).

To Conclude…

…Who’s got the power?

Another great entry! I love the format of replying to the blog from the previous post. Makes it so easy to read and make me want to read on. One question I have: Most of the strategies names have been top down? Do you think bottom up approaches could provide a better solution? Are there any case studies which you know of which GERD could take influence from?

ReplyDeleteAn example which I remember is Zai in Burkino Faso. The documentary I watched called 'The Man Who Stopped the Desert' touched on a farmer from Burkina Faso, who stopped desertification in his village in by working together with his family to plant trees which have now grown into a vast forest. Initially, policy leads and farmers ridiculed him. In short, he transformed a forty-hectare desert into a thriving forest. So I believe sometimes the people of the land understand the characteristics and needs to the land more than professionals- governments should work to empower these communities with the tools they need to unlock their potential or least involve them in the process

Delete