WALK A NILE IN MY SHOES

Throughout this blog, I will be tackling the interconnected issues of food and water, particularly the effects of dams on food production, to understand the nuances of transboundary water use, because of course, to grow food, you must have water.

I've decided that the best way to begin this blog is to look at my existing knowledge on food and water. This largely comes from studying Surface Hydrology and Groundwater in second year and examining the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands, including the effects of the 1974 construction of the Tiga Dam there, bringing me to my topic; Dams.

Around 60% of the African population lives within a transboundary river basin (Nijsten et al. 2018). The asymmetrical interconnected nature of the quality and quantity of water in these basins is a major cause of conflict, with upstream riparian states influencing flows for downstream riparians. Questions surrounding the rights and sovereignty of the use of international water have been long rooted in politics, however, how does one develop guidelines for allocating a vital resource which is mobile, which fluctuates in time and in space, and which ignores political boundaries? (Wolf 1999:3). The formation of an ‘equitable water-sharing agreement along waterways is a prerequisite to hydro-political stability’ (ibid:3).

The Nile Basin

The Nile flows from south to north to 11 countries, shared by about 400 million people, which is forecasted to double and advance 1 billion by 2050 (Siam & Eltahir 2017). The Nile is compromised in 10 different sub-basins, with two main branches: the White Nile and the Blue Nile.

Average annual rainfall of the Nile (Atlas.NileBasin, 2021)

Spatial and Temporal Precipitation Patterns

The Blue Nile provides the main input, however fluctuates seasonally. Spatially, precipitation generally increases from north to south and with elevation (Beyene et al, 2007). As seen in Figure 1, the arid parts of northern Sudan and Egypt have a minimum rainfall of less than 50mm, which reduces river flow, down to increased evaporation. And the highest levels have been recorded in the equatorial lakes region near Lake Victoria and the Ethiopian highlands, which represents a major source to the Nile. (Atlas.NileBasin, 2021). Siam & Eltahir (2017) found inter-annual variability of total Nile flow may climb by 50% (35%) according to projections from climate model simulations.

Damns in Africa

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) (Water & Power, 2020)

In accordance to Falkenmark’s water stress index, which is heavily relies on surface water sources such as the Nile river, North Africa is a water-stressed region. Eygpt was the first of its African peers to jump onto the global dam-building movement of the late twentieth century. With over 97% of Egypt’s water supplied by the Nile, it was crucial they created an efficient management system of the river, which was attempted with the construction of the Aswan Dam. Following its completion in 1975 it supplied half of the Egyptian power supply and increased the amount of cultivable land by 20% (Piesse, 2018), however it also slows the flow of the Nile to a drop by the time it reaches the key rice-growing delta, marking the start of Africa’s dam flaws and flows.

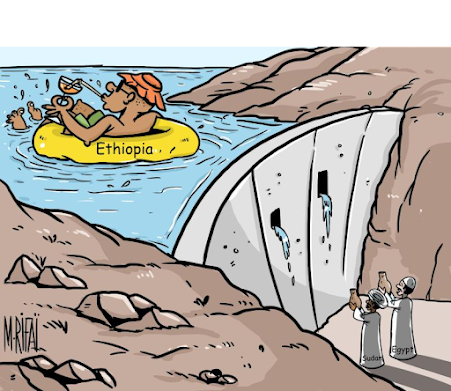

It is apparent dams have restructured Africa’s food industry, as in the last 50 years to 2000, irrigation nearly tripled, in part due to the construction of storage dams (Soloman, 2011). The largest of these African dams is the $4.5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), constructed in 2011. To Ethiopians, the dam symbolises a catalyst in confirming Ethiopia’s place as a rising African power. With an expected capacity of 6,000MW, the mega project will light up millions of homes and earn billions from electricity sales to neighbouring countries. However, for Egypt the 74 billion m3 capacity of the reservoir, equating to over 40% of Egypt’s total annual Nile supply, GERD is an opportunity for Ethiopia to seriously disrupt Egypt’s supply (Gebreluel, 2014). The politics of the GERD is rooted in how it might rearrange the distribution of Blue Nile flows, and in turn food production.

My blog will focus on water and food, however the transdisciplinary nature of dam construction, especially in the fickle Nile, I will also be focusing on the politics of water. Over the next few posts, I will be focussing on the GERD, and its possible implications on irrigated agriculture, before delving deeper into the broad hydropolitics of water and food within the Nile basin.

Throughout this blog, I will be tackling the interconnected issues of food and water, particularly the effects of dams on food production, to understand the nuances of transboundary water use, because of course, to grow food, you must have water.

I've decided that the best way to begin this blog is to look at my existing knowledge on food and water. This largely comes from studying Surface Hydrology and Groundwater in second year and examining the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands, including the effects of the 1974 construction of the Tiga Dam there, bringing me to my topic; Dams.

Around 60% of the African population lives within a transboundary river basin (Nijsten et al. 2018). The asymmetrical interconnected nature of the quality and quantity of water in these basins is a major cause of conflict, with upstream riparian states influencing flows for downstream riparians. Questions surrounding the rights and sovereignty of the use of international water have been long rooted in politics, however, how does one develop guidelines for allocating a vital resource which is mobile, which fluctuates in time and in space, and which ignores political boundaries? (Wolf 1999:3). The formation of an ‘equitable water-sharing agreement along waterways is a prerequisite to hydro-political stability’ (ibid:3).

The Nile Basin

The Nile flows from south to north to 11 countries, shared by about 400 million people, which is forecasted to double and advance 1 billion by 2050 (Siam & Eltahir 2017). The Nile is compromised in 10 different sub-basins, with two main branches: the White Nile and the Blue Nile.

Average annual rainfall of the Nile (Atlas.NileBasin, 2021)

Spatial and Temporal Precipitation Patterns

The Blue Nile provides the main input, however fluctuates seasonally. Spatially, precipitation generally increases from north to south and with elevation (Beyene et al, 2007). As seen in Figure 1, the arid parts of northern Sudan and Egypt have a minimum rainfall of less than 50mm, which reduces river flow, down to increased evaporation. And the highest levels have been recorded in the equatorial lakes region near Lake Victoria and the Ethiopian highlands, which represents a major source to the Nile. (Atlas.NileBasin, 2021). Siam & Eltahir (2017) found inter-annual variability of total Nile flow may climb by 50% (35%) according to projections from climate model simulations.

Damns in Africa

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) (Water & Power, 2020)

In accordance to Falkenmark’s water stress index, which is heavily relies on surface water sources such as the Nile river, North Africa is a water-stressed region. Eygpt was the first of its African peers to jump onto the global dam-building movement of the late twentieth century. With over 97% of Egypt’s water supplied by the Nile, it was crucial they created an efficient management system of the river, which was attempted with the construction of the Aswan Dam. Following its completion in 1975 it supplied half of the Egyptian power supply and increased the amount of cultivable land by 20% (Piesse, 2018), however it also slows the flow of the Nile to a drop by the time it reaches the key rice-growing delta, marking the start of Africa’s dam flaws and flows.

It is apparent dams have restructured Africa’s food industry, as in the last 50 years to 2000, irrigation nearly tripled, in part due to the construction of storage dams (Soloman, 2011). The largest of these African dams is the $4.5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), constructed in 2011. To Ethiopians, the dam symbolises a catalyst in confirming Ethiopia’s place as a rising African power. With an expected capacity of 6,000MW, the mega project will light up millions of homes and earn billions from electricity sales to neighbouring countries. However, for Egypt the 74 billion m3 capacity of the reservoir, equating to over 40% of Egypt’s total annual Nile supply, GERD is an opportunity for Ethiopia to seriously disrupt Egypt’s supply (Gebreluel, 2014). The politics of the GERD is rooted in how it might rearrange the distribution of Blue Nile flows, and in turn food production.

My blog will focus on water and food, however the transdisciplinary nature of dam construction, especially in the fickle Nile, I will also be focusing on the politics of water. Over the next few posts, I will be focussing on the GERD, and its possible implications on irrigated agriculture, before delving deeper into the broad hydropolitics of water and food within the Nile basin.

This a great starting entry Laiba! Love the use of statistics to back up your points and great clear subheadings. One question you may not have touched on thus far; how you do think you will, as an academic writer, prevent harmful representations of Africa in your blog? I look forward to reading your following posts!

ReplyDeleteHey Elena! Thanks for the comment and great question - Having read Binyavanga Wainaina's 2006 'guide' on [how to write about Africa](https://granta.com/how-to-write-about-africa/), in which she highlighted the racist and colonial depictions of Africa that have been perpetuated in Western discourses, I believe as academic writers, we need to work to exclude the system of “linguistic, semiotic and symbolic references” that descriptions of sub-Saharan Africa have been reduced to (Nothias, 2018)

DeleteThus, As a non-African person, I aim to reflect on this article to consider how I can prevent my writing from reproducing harmful stereotypes as part of a wider goal of decolonising knowledge production about sub-Saharan Africa.